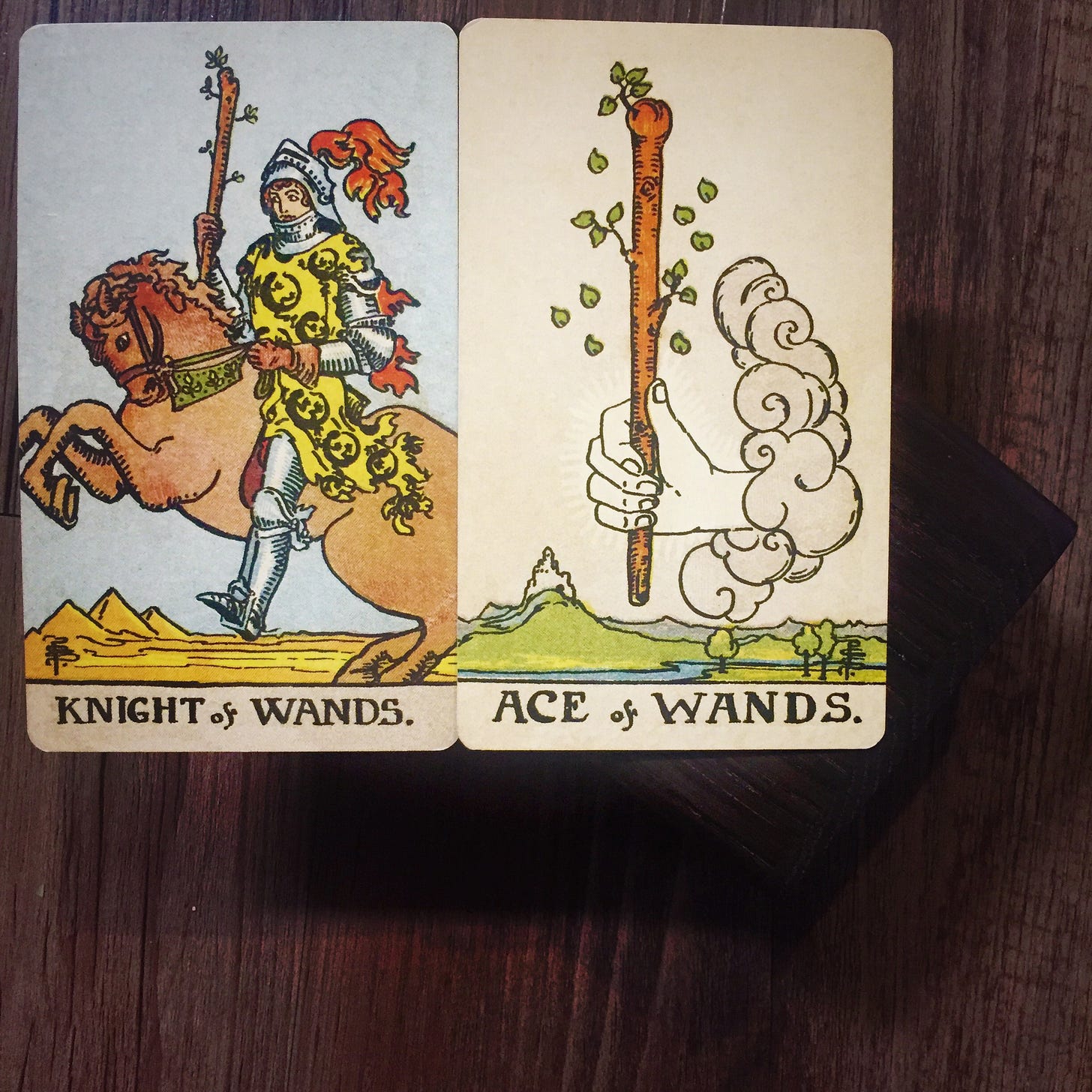

The Waite-Smith deck set the gold standard of wands being associated with the element of fire without portraying a single flame. It’s one of Smith’s most clever innovations, using two motifs: the imagery of salamanders in the periphery and clothing of the courts, as well as the presence of leaves on the fashioned wood, many of which aren’t even connected to the wand by stems:

Smith’s wands contain the potential energy to burn, but they also contain vitality, the unseen ability to impose upon the world and alter it.

Before Lavoisier, chemists tended to believe that fire was a substance unto itself, or at least, that there was something called phlogiston that glowed when it was released from a substance through burning. We know now that there is no such thing: any matter burned under experimental observation actually gains mass, and the weight that the process of burning adds has come to be known as oxygen.

It was the exact opposite of what chemists expected to prove. This was one of the foundational experimental results that created the modern passion for skepticism: the decisive proof that elemental fire (as phlogiston) wasn’t “real.” While it was obvious by this time that the world was not simply a product of four types of atom, this discovery allowed the weirdness of the highest element of fire (as an organizing principle) to expand in understanding over the next few centuries.

Fire is not actually matter, but reaction as object: it is observable, non-matter material, an event that changes reality and has form, but no mass in and of itself. A flame is the simplest and most aesthetically clear expression of the thermodynamic.

Still, Smith took its portrayal a step further, to wands as still-living, non-burning wood. This decision expresses vital experience: passion, will, motion, ideology, and belief; the instigating stuff that is material, but is not matter in and of itself, just like fire. It is the animistic and animating in equal measure, expressed as suspended animation. Its mutability is in time, rather than space (which is the domain of air). It will grow, it will branch, and someday, it will rot or burn. But for now, it is this.

The Carnival at the End of the World Tarot showcases this with an amusing, cartoonish gag: a beaver chews through the Ace of Wands as though it is the trunk of a tree, and afterwards, stares in bewilderment as the remainder burns in midair:

As the adjacent Madame Lulu’s Book of Fate puts it:

“The maker’s marks meet creative sparks and the results are born aloft: it is an auspicious time for beginning an artistic project or any new collaboration between beings, matter and the invisible.”

Here, the wood is also on fire, yet still alive, and actively refusing to transition from arbor to lumber. It is one of the most transcendent (and defiant) expressions of the suit of wands: the wood was never the point. Remove it from the equation, and you still have the actual stuff of the suit, beyond sight or print.

Herein is a “secret” expressed in Smith’s Ace of Wands: if the mysterious hand were to let go, the wand itself would remain in place.