MISSIVE 54

The Knight of Swords as a Tornado Chaser

Tornadoes are the only extant species of kaiju: city-killing monsters with a nature beyond our fathoming, towering over all manmade things. To behold one in person is to know a unique kind of horror that is impossible to digitally communicate. They are children of the great anvil clouds that descend from the Rocky Mountains to maintain the prairie’s emptiness through apocalyptic winds and hail. Perhaps they hatch from eggs deep within mountain caves, to be carried forward across North America by cold fronts while they mature from some yet-unseen larval state.

Despite their lack of biochemical composition, it is difficult to observe one and not understand that it is a living thing, however confused and short-lived. They have their own convection-based metabolism, their own serpentine skin wrought from soil and vapor, and some even have internal organs, if their size demands additional vortices. But most importantly, through their rotation, they have their own visages: wherever you stand relative to one’s motion, you can see and feel that it hungers to swallow you. It always seems to be getting closer, whether or not it actually is.

In 2015, I found myself in this position on the border of Nebraska and Wyoming, overtaken by an abruptly-formed cumulonimbus while trying to make Cheyenne by nightfall. I knew I’d made a serious mistake when I could see the hook echo on the weather radar. Before the rain hit, a wall of dust rose on the left side of my car, and on the right, a great whorl connected with a terrible protrusion emerging from the sky. There are no sirens this far from any towns, but you know it when you see it.

There are rules for dealing with tornadoes that you learn growing up on the prairie. Basements and bathrooms are ideal hiding places if you’re not in a mobile home; otherwise, you’ll need to find a storm shelter. If you’re on the road, the folk wisdom is to find a highway overpass, climb into one of its concrete alcoves, and hope the suction from a differential in air pressure doesn’t drag you out screaming. Out where I was, there were no crossroads, no places for intersection; just sky, road, and dust. It’s hard to emphasize how empty this border region is. This photo was taken on the far side of the encounter, after I’d survived:

There was only one option for me, and it was to step on the gas. My best bet was to hope like hell nothing was in my way and charge headlong towards whatever fate I-80 offered. Far enough in, thick, white sheets of rain obscured my vision more intensely than any fog would have. Eyes forward, unsure of what the hell I’d do if I saw the red of tail lights. Eventually, I did. I slowed down. So did the rain. The sun cut through.

—

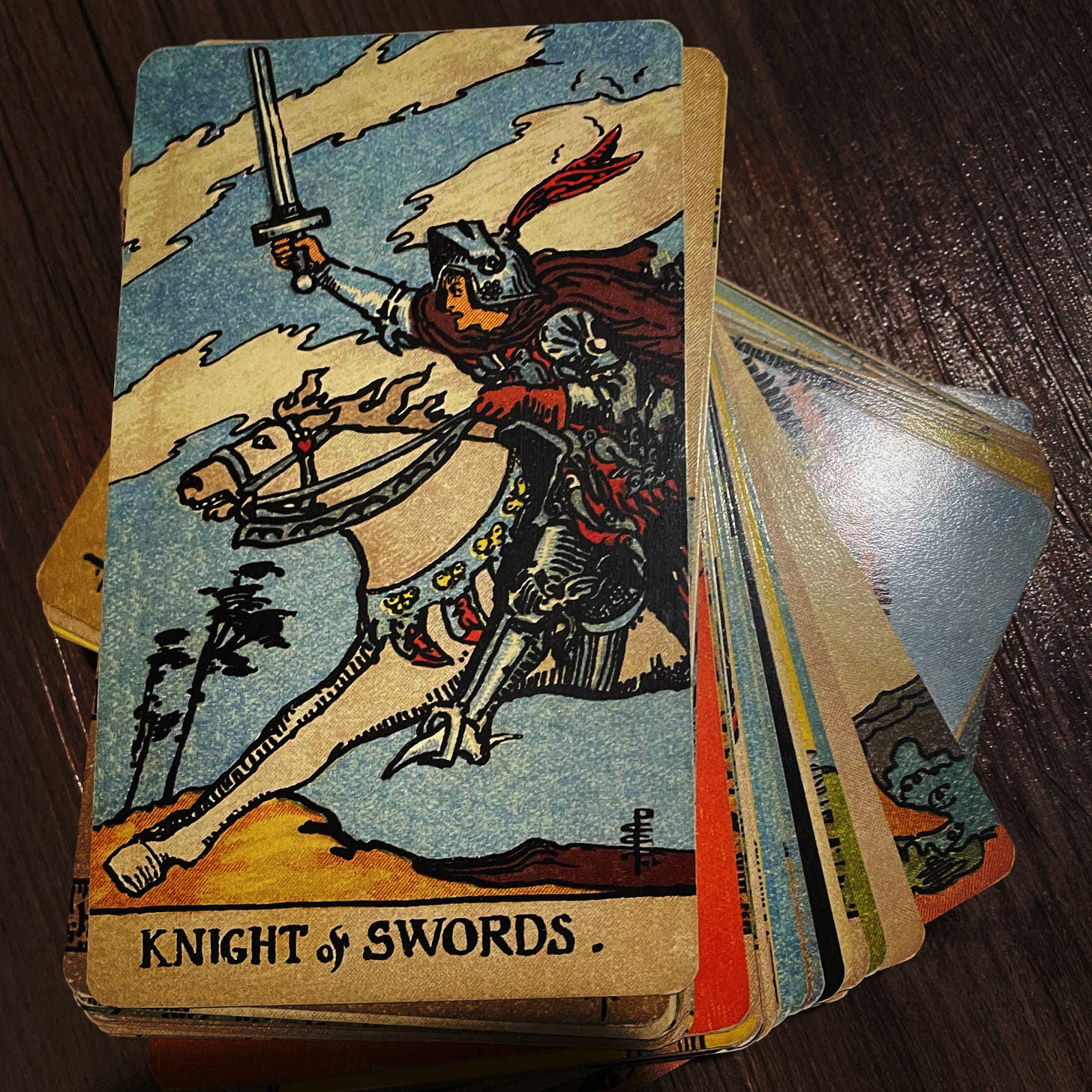

The Knight of Swords is often portrayed as the most brash and reckless among his ilk, charging headlong into more than he can handle. Take another look at the horse in the classic Waite-Smith. It is scared shitless:

I’ve always found this to be a difficult-to-parse association. With Swords as the suit of intellect, one would expect the Knight of Swords to be the most clever among his ilk, rather than the most likely to spook his mount into bucking him into a wall of spears. But as the Air of Air, he embodies intellect for its own sake: strategy and mind applied to problems where the mind does not matter. We can see extreme winds pressing against him; for all we know, he is indeed charging towards a tornado.

Given this, and my own personal experience, I love the Spolia Tarot’s abstraction:

This deck’s Knight of Swords is a capital-Q Quixotic figure, ready to charge directly at a tornado, and fight it through confidence in his own ability to outsmart the nightmare. The whirlwind is superior to its human challenger in every way except one, but only a human being would imagine that this singular difference, intellect, will actually change the outcome of the battle. Where I ran away, he refuses.

The Knight of Swords cannot win, but he also cannot be convinced that he cannot win. He embodies every single instance where man believes he can outfox reality. This is almost always not true, but the sliver of times it has been propels humans to imagine their intellect holds more absolute authority than it actually does. Tarot calls out this folly, and asks, slyly, to consider other angles. Being smart enough isn’t enough, and thinking it is often tends to be more foolish than not thinking about the problem at all.

When this Knight appears in a reading, pay attention to the horse. Whatever the former is charging towards, the latter, bound to the world by its hooves rather than suspended above it, knows the stakes. What good is being smarter than a tornado? Or, perhaps more topically, a virus? Consider also phenomena like the Dunning-Kruger effect; people often think they can solve big problems, or survive things, that they actually cannot. There are three other suits to consider when engaging with any problem of scale, and Swords alone will never suffice.