MISSIVE 6

The Fool, Videodrome, and the Threshold of Epistemological Collapse

I have thought much on this stranger observed from Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner, who was quietly contemplating a blank-yet-searingly-bright display just outside Anaheim. The screech of the train’s brakes did not disturb him. Even in the absence of visible advertising, something about that screen brought him peace; maybe it was that lack of content, the relief of an emptiness where the medium could show through.

One of the motifs of The Fool is the unseen point of no return. By the time he is aware of the cliff’s edge, he is already falling.

The Fool in the photograph is facing away from the obvious precipice of the tracks, unaware that he is facing another that he has already crossed. He, himself, is being converted into digital content by yours truly:

The train window was filthy, but it added its own character to the photograph. It reminded me of the importance of the frame itself, the device taking it, the tailoring of the photo in Afterlight, and how many degrees of filter and abstraction existed between the moment being witnessed and its communicable meaning.

“The medium is the message.”

In David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, there is no separation between the physical world and visual media. A “new flesh” comes into being once television signals are capable of altering the human body, producing tumors and new orifices. The character of Brian O’Blivion (widely understood to be a fictional stand-in for Marshall McLuhan), exists within the threshold of television and the real, and explains the situation to the protagonist, Max, as follows:

“The battle for the mind of North America will be fought in the video arena -- the videodrome. The television screen is the retina of the mind's eye. Therefore the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore television is reality, and reality is less than television.”

O’Blivion is shortly thereafter murdered in both worlds by Debbie Harry’s character, Nicki, who anatomically fuses with Max’s television, becoming a pair of lips on the screen that he kisses and becomes one with. The boundary between the virtual and physical is revealed to be illusory in a moment of strange communion between them.

I was surprised when my Moon Power Tarot arrived to find a reflection of the Videodrome motif, augmenting this piece that I was already planning to write strictly based on prior photography:

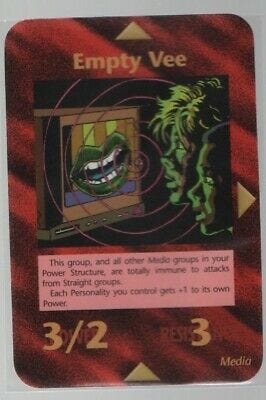

This image has been around. I’d be remiss not to note it’s also in the conspiracy theory darling Illuminati card game as “Empty Vee” (see also, MTV), furthering the empty-head/zero construction of the Fool:

Today, the archetypal screen is no longer driven by cathode-ray tube, but rather, by a synthetic substance branded as liquid crystal. Videodrome’s horror, now dated and hard to recognize, has come to pass: our ‘phones’ are barely phones at all: instead, they are external sensory organs, tiny two-way televisions that must be carried at all times to function, as though part of the human body.

Every act is one of both broadcast and experience. The person and personal brand are one. Messages contain imprints that indicate whether or not they have been touched by eyes. Notifications replicate the experience of an itch. All personal spaces, including bodies, are posed and decorated so as to be consumable: photography could happen at any moment, and can never be fully undone once released to the network.

Epistemology has been reduced to boolean ooze, with the age of machine learning rapidly usurping the powers of photoshop and CGI, which, in turn, were once considered revolutionary compared to the doctoring and special effects that came before them. Total indistinguishability is on the horizon. It is likely already here.

We must now live with the possibility that anything experienced as reality is cut whole from liquid crystal cloth, regardless of its origin or authority. We weren’t ready for this world. We crossed the threshold of the screen without noticing, and fell head-first into virtual permanence. The pandemic isn’t helping; so long as it continues, the internet is the only safe place where reality can be found.

We can never log off. Long live the new flesh.